Introduction to LMAX Disruptor: A high-performance inter-thread communication framework

LMAX Disruptor is an open-source inter-thread communication framework designed for high concurrency and low latency scenarios. This article introduces its core concepts and design principles, compares the performance bottlenecks of Java's built-in queues, and explains key technologies such as circular buffers, lock-free design, and cache line padding to help understand its high-performance implementation principles.

1. Background: Why Do We Need Disruptor?

Disruptor was developed by the UK foreign exchange trading company LMAX, originally intended to solve the latency issues of memory queues in high-concurrency scenarios. Traditional lock-based queues can cause significant performance bottlenecks and latency jitter in multi-threaded environments due to lock contention. The LMAX team discovered that the latency of queue operations could even rival that of I/O operations when building a high-performance financial trading platform.

Based on this pain point, Disruptor was born. It is a high-performance inter-thread communication queue focused on solving the efficiency issues of inter-thread communication, rather than inter-process communication like Kafka. With its excellent design, systems based on Disruptor can handle up to 6 million orders per second per thread. This achievement made it famous at the QCon conference in 2010, earning a special write-up from enterprise application software expert Martin Fowler and the Duke Award from Oracle. Today, many well-known projects, including Apache Storm, Camel, Log4j 2, and HBase, have adopted Disruptor to enhance performance.

2. Introduction to Disruptor

In terms of usage, Disruptor is similar to Java's built-in BlockingQueue, both used for passing data between threads. However, Disruptor has some unique features that make it far superior in performance:

- Multicast to Consumers: The same event can be processed by multiple consumers, and consumers can execute in parallel or form dependencies.

- Pre-allocated Memory: All event objects in Disruptor are pre-allocated at startup, avoiding runtime dynamic memory allocation and garbage collection (GC) pauses.

- Optional Lock-free Design: In a single-producer scenario, Disruptor can completely avoid using locks, eliminating the overhead caused by lock contention.

3. Core Concepts

To understand how Disruptor works, it is essential to grasp its several core concepts:

- Ring Buffer: This is the core data structure of Disruptor, a pre-allocated array of fixed size. Being an array, its continuity in memory is very friendly to CPU caches.

- Sequence: Each producer and consumer maintains its own sequence to track its processing progress. The sequence is key to ensuring correct data transfer between threads. The

Sequenceobject internally uses cache line padding to avoid false sharing issues. - Sequencer: The core of Disruptor, responsible for quickly and correctly transferring data between producers and consumers. It has two implementations:

SingleProducerandMultiProducer, both of which are parallel algorithms. - Sequence Barrier: Created by the

Sequencer, it coordinates the dependencies between consumers and determines which data can be consumed. - Wait Strategy: When consumers are faster than producers, they need to wait for new events. The wait strategy defines how consumers wait, such as through

BlockingWaitStrategy(locking),SleepingWaitStrategy(sleeping),YieldingWaitStrategy(yielding CPU), orBusySpinWaitStrategy(busy waiting). - Event: The unit of data flowing in Disruptor. It is a regular Java object defined by the user.

- EventProcessor: The main loop that processes events, continuously monitoring and handling new events in the Ring Buffer.

BatchEventProcessoris its primary implementation. - EventHandler: An interface implemented by the user, representing the specific business logic of consumers.

- Producer: The thread responsible for publishing events to Disruptor.

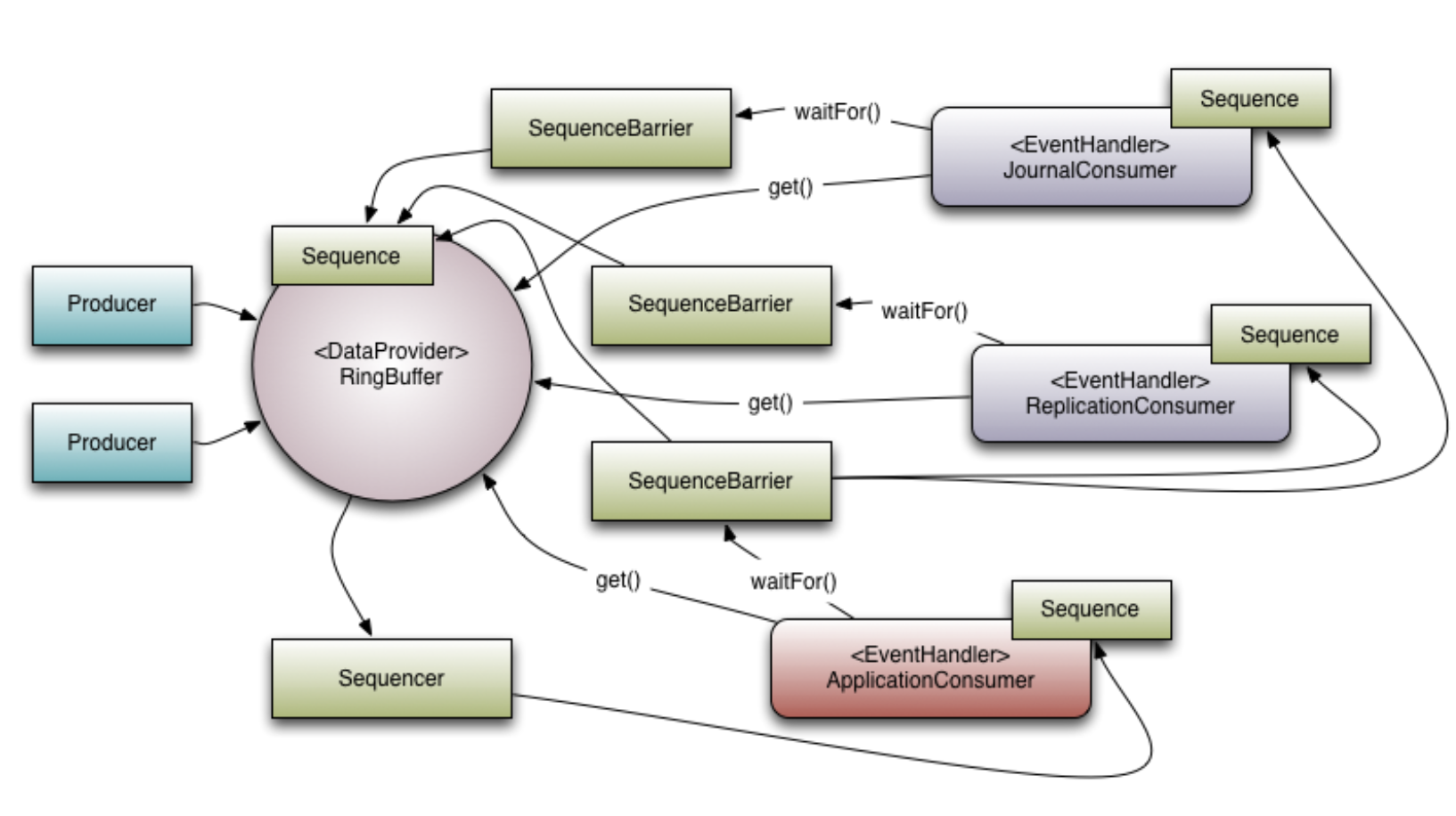

The following diagram shows how these components work together:

4. Comparison with Java Built-in Queues and Performance Bottleneck Analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the advantages of Disruptor, we will compare it with the commonly used ArrayBlockingQueue in Java.

4.1 Overview of Java Built-in Queues

| Queue | Bounded | Lock | Data Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

ArrayBlockingQueue | bounded | locked | arraylist |

LinkedBlockingQueue | optionally-bounded | locked | linkedlist |

ConcurrentLinkedQueue | unbounded | lock-free | linkedlist |

LinkedTransferQueue | unbounded | lock-free | linkedlist |

PriorityBlockingQueue | unbounded | locked | heap |

DelayQueue | unbounded | unbounded | heap |

ArrayBlockingQueue is a typical bounded queue based on arrays, ensuring thread safety through locking. While lock-free queues like ConcurrentLinkedQueue offer better performance, they are unbounded and can lead to memory overflow in scenarios where the producer's speed far exceeds that of the consumer. Therefore, ArrayBlockingQueue is often a fallback option in scenarios requiring a bounded queue with performance considerations. However, it has the following performance bottlenecks:

4.2 Locking

Locking is the primary performance bottleneck of ArrayBlockingQueue. Threads can be suspended and resumed due to lock contention, resulting in significant context-switching overhead. If a thread holding a lock experiences a page fault or is delayed by the scheduler, all threads waiting for that lock will stall, severely impacting system throughput.

Experimental Comparison:

A simple experiment can intuitively demonstrate the overhead of locking. Incrementing a 64-bit counter in a loop for 500 million times:

| Method | Time (ms) |

|---|---|

| Single thread | 300 |

| Single thread with CAS | 5,700 |

| Single thread with lock | 10,000 |

| Single thread with volatile write | 4,700 |

| Two threads with CAS | 30,000 |

| Two threads with lock | 224,000 |

The data shows that whether in single-threaded or multi-threaded scenarios, locking performs the worst. In multi-threaded contexts, using CAS (Compare-And-Swap) significantly outperforms locking.

Difference Between Locking and CAS:

- Locking: A pessimistic strategy that assumes conflicts will always occur, so it locks before accessing shared resources, forming a critical section that only one thread can enter. The

offermethod ofArrayBlockingQueueis implemented usingReentrantLock. - Atomic Variables / CAS: An optimistic strategy that assumes no conflicts. Threads directly attempt to modify data using CPU-level atomic instructions (CAS) to ensure the atomicity of operations. If the data is modified by other threads during the operation, the CAS operation will fail, and the thread typically retries through spinning or other means until successful.

In low contention scenarios, CAS usually outperforms locking. However, in high contention environments, extensive CAS spinning retries can also consume significant CPU resources. Nonetheless, in most real-world scenarios, atomic variables generally perform better than locks and do not lead to deadlock or liveliness issues.

4.3 False Sharing

This is another critical factor affecting performance, often overlooked. Modern CPUs have multi-level caches (L1, L2, L3) to enhance performance. Data is transferred between main memory and CPU caches in cache line units, typically 64 bytes.

When a CPU core modifies data in a cache line, to maintain data consistency, copies of that cache line in other CPU cores must be marked as "invalid." This means that any other core needing to access any data in that cache line must reload it from main memory, incurring significant performance overhead.

False sharing occurs here: if multiple threads modify variables that are logically independent but physically located in the same cache line, then a modification by one thread to one variable will invalidate the cache line for other threads, even if they are operating on different variables.

In ArrayBlockingQueue, there are three key member variables: takeIndex (consumer pointer), putIndex (producer pointer), and count (number of elements in the queue). These three variables are likely to be allocated in the same cache line. When the producer puts an element, it modifies putIndex and count; when the consumer takes an element, it modifies takeIndex and count. This operational pattern leads to frequent invalidation of each other's cache lines between producer and consumer threads, causing severe performance degradation.

Solution: Cache Line Padding

A common method to solve false sharing is cache line padding. By padding some useless data before and after the variables that need isolation, these variables can be forced to be allocated in different cache lines, thereby avoiding mutual interference.

After JDK 8, Java officially provides the @Contended annotation to help developers elegantly solve false sharing issues, automatically performing cache line padding.

5. Disruptor's Design Solution: Pursuing Extreme Performance

Disruptor overcomes the performance bottlenecks of traditional queues through a series of ingenious designs.

-

Ring Array Structure: It uses an array instead of a linked list to leverage its memory continuity, which is extremely friendly to CPU caches. All event objects are created and placed in the Ring Buffer at initialization, achieving object reuse and significantly reducing GC pressure.

-

Element Positioning:

- The length of the Ring Buffer is designed as a power of 2, allowing for quick element positioning using bitwise operations (

sequence & (bufferSize - 1)) instead of modulo operations (sequence % bufferSize), which is more efficient. - The index (

sequence) uses alongtype, which will take hundreds of thousands of years to overflow even at a processing speed of millions of QPS, eliminating concerns about index overflow.

- The length of the Ring Buffer is designed as a power of 2, allowing for quick element positioning using bitwise operations (

-

Lock-free Design:

- Single Producer Scenario: In single-producer mode, the producer can request write space without locks. Since it is the only writer, it knows the next available position without competing with other threads.

- Multi-producer Scenario: In multi-producer scenarios, Disruptor uses CAS to ensure thread-safe requests for write space. Each producer thread attempts to "declare" the range of sequences it will use through CAS operations.

- Consumers: Consumers determine which data is readable by tracking the sequences of producers and other dependent consumers, and this process is also lock-free.

-

Solving False Sharing Through Sequence: Core states in Disruptor, such as the producer's

cursorand the consumers'sequence, are encapsulated inSequenceobjects. These objects use cache line padding techniques, filling multiplelongtype useless variables before and after the corevaluefield, ensuring that eachSequenceobject occupies one or more cache lines, fundamentally avoiding false sharing issues. -

Object Header and Memory Layout: Disruptor's design also fully considers the JVM's object memory layout. A Java object in memory consists of an object header (Header), instance data (Instance Data), and padding (Padding). The object header contains the Mark Word (for storing hash code, GC information, lock information, etc.) and type pointer. Through clever cache line padding, Disruptor ensures that its core

Sequencevalues do not share the same cache line with other potentially modified data when loaded into the CPU cache, ensuring performance.

6. Conclusion

Disruptor achieves a series of extreme performance optimizations through a deep understanding of the underlying hardware principles. It effectively addresses the lock contention and false sharing issues of traditional queues in concurrent scenarios through techniques such as ring arrays, lock-free CAS, and cache line padding, providing extremely high throughput and low latency. Although its usage is somewhat more complex than Java's built-in queues, Disruptor is undoubtedly a powerful tool worth considering in systems with stringent performance requirements.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!